the author-centered workshop

When I started leading writing workshops, I knew I wanted to lead a different kind of workshop than the ones I’d experienced in my Masters program.

In those classes, I’d found myself frustrated by the male-dominated conversations and the focus on highbrow, realistic fiction as the ideal form of writing. As a woman writer interested in magical realism and young adult literature, these workshops often didn’t seem like a welcoming place for me.

So when I began leading workshops of my own, I was determined to make them more open-minded, supportive, and inclusive for writers. However, what I didn’t fully realize was that—despite striving to make my workshops different—I was still re-enacting a workshop model developed by white male writers for white male writers.

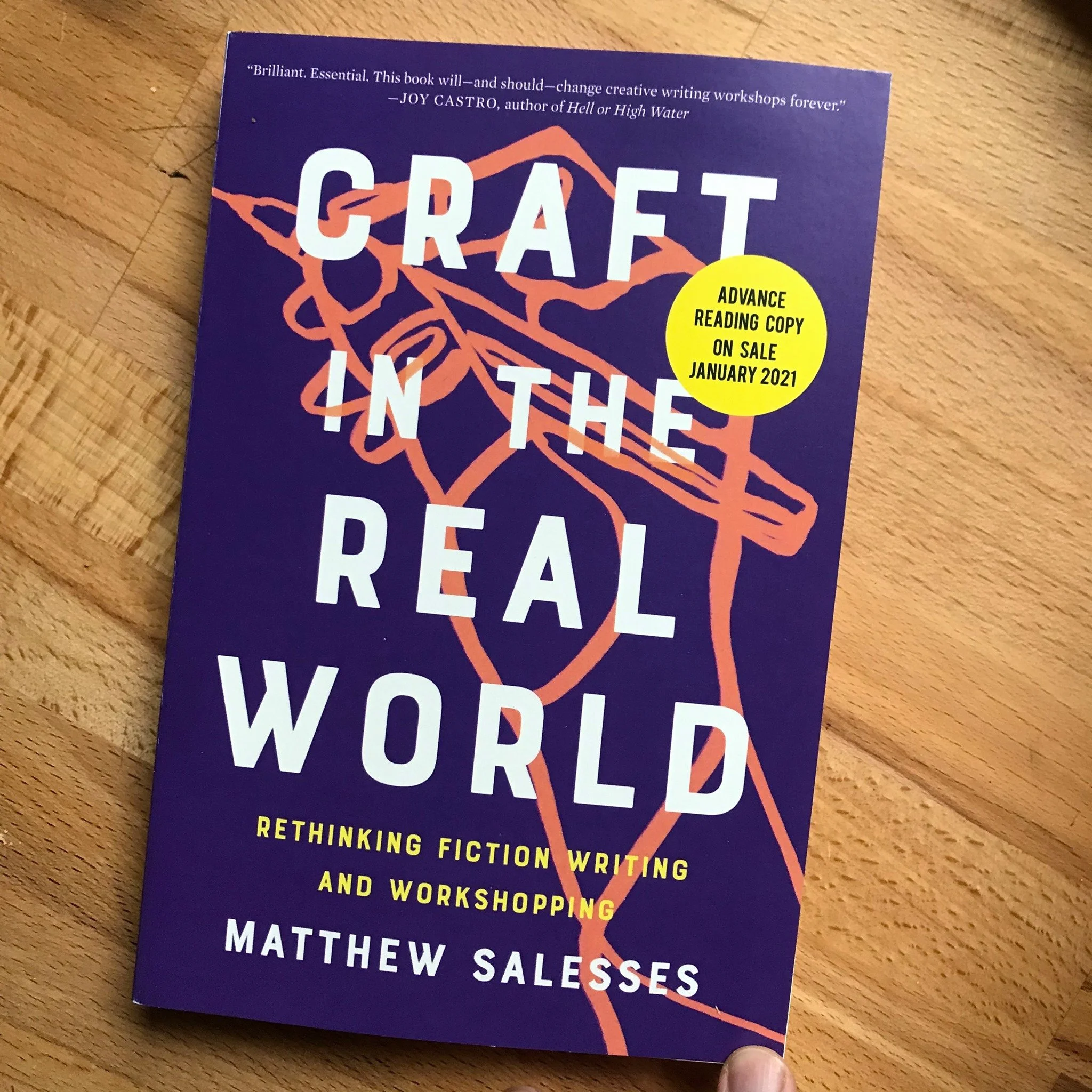

It wasn’t until I read Matthew Salesses’ book Craft in the Real World that I fully recognized how the traditional workshop model was perpetuating practices that didn’t make sense for me and my teaching philosophy.

For example, why did writers have to stay silent in class while their work was discussed? Couldn’t better and more helpful conversations arise from an open dialogue between writers and readers?

And why did workshops critique first drafts of stories as if they were final drafts, offering advice for revision while authors were still figuring out what their story was about? Wasn’t it better to ask questions to help the writer clarify their meaning rather than push the writer in a certain direction?

Matthew’s book inspired me to change the way I teach workshops. (And I highly recommend his book to any writing teacher or student who has experienced uncomfortable or downright damaging workshops.)

Now, instead of simply using the workshop model handed to me as an MFA student, I embrace alternative workshop models that generate more insightful conversations and help both readers and writers have more meaningful, uplifting workshop experiences.

A few gems from Craft in the Real World:

“It is the instructors’ responsibility to remake things—and that starts with burning the old models down.”

“If we must be willing to risk ourselves in our writing, we must be willing to risk ourselves in how we teach writing. It is time for workshop to change.”

“What we call craft is in fact nothing more or less than a set of expectations. Those expectations are shaped by workshop, by reading, by awards and gatekeepers, by biases about whose stories matter and how they should be told. …The more we know about the context of these expectations, the more consciously we can engage with them.”

“I believe in workshop as a shared act of imagination, in the ability of many minds to foster the growth of one by one by one through conversation. I believe in the vulnerability of process and the process of vulnerability.”