what does writing mean in a world on fire?

If you're anything like me, you've been struggling with the collective pain and exhaustion in the world right now – not just the Roe v. Wade overturn (although that's certainly been dominating my headspace over the past week), but also gun violence, the climate crisis, the ongoing pandemic, and more.

This past week pushed me into a state of overwhelm where it was difficult to focus on writing – or to even find the meaning in writing at all.

I spent most of the weekend feeling terribly low, compulsively reading the news and feeling exhausted by the triple-digit heat that has enveloped Austin since early June.

But when the heat wave finally broke on Monday, with a rainstorm that felt like a much-needed reprieve, I happened to remember this beautiful essay by Rebecca Makkai, which had helped anchor me in the early days of the pandemic.

Rereading it, I was reminded why writing is still important – especially important – right now, when things feel Very Dark Indeed.

I've included my favorite sections of her essay below, in the hopes that it also helps you restore some of your hope and faith and creative fire this month.

"The idea that art is born of leisure, during times of peace, is a simplistic romance, a non-artist’s daydream. (Wouldn’t it be nice to just be creative all day? In a cabin? With the tea and whatnot?) Someone recently asked if I need to be in a meditative state in order to write. Jesus, no. I write best angry. Don’t you? I write best desperate, I write best heartbroken, I write best with my pulse throbbing in my neck. Even in the best times, many of us read and write to confront the world and its failings, not to escape the same.

Listen: Ngūgiī Wa Thiong’o wrote an entire novel on toilet paper in his prison cell. Before her death at Auschwitz, Irene Nemerov wrote Suite Française in microscopic handwriting in a single notebook. Anna Akhmatova’s apartment was bugged and her books pulped, but she’d write her poems out for visitors on small slips of paper, wait till they’d memorized them, then burn the papers in the stove. And no, it’s not always political art we fight for. H. A. and Margaret Rey fled Paris in 1940 on bicycles they’d made themselves, carrying with them the manuscript of Curious George."

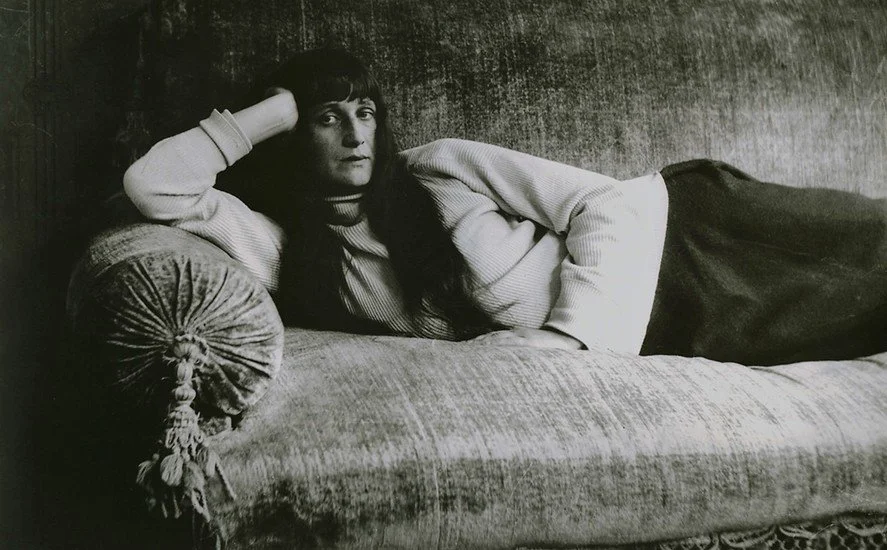

The poet Anna Akhmatova

"My new novel, which I’ve been out on the road promoting (yes, instead of canvassing, instead of marching) since the midpoint of this surreal year, largely chronicles the AIDS epidemic in 1980s Chicago. One of the lessons hammered in by my research was how both art and humor sustained a group weary from a lifetime of fighting, and the fight of a lifetime. And, more — how effective that art and that humor were, as both shields and weapons of attack.

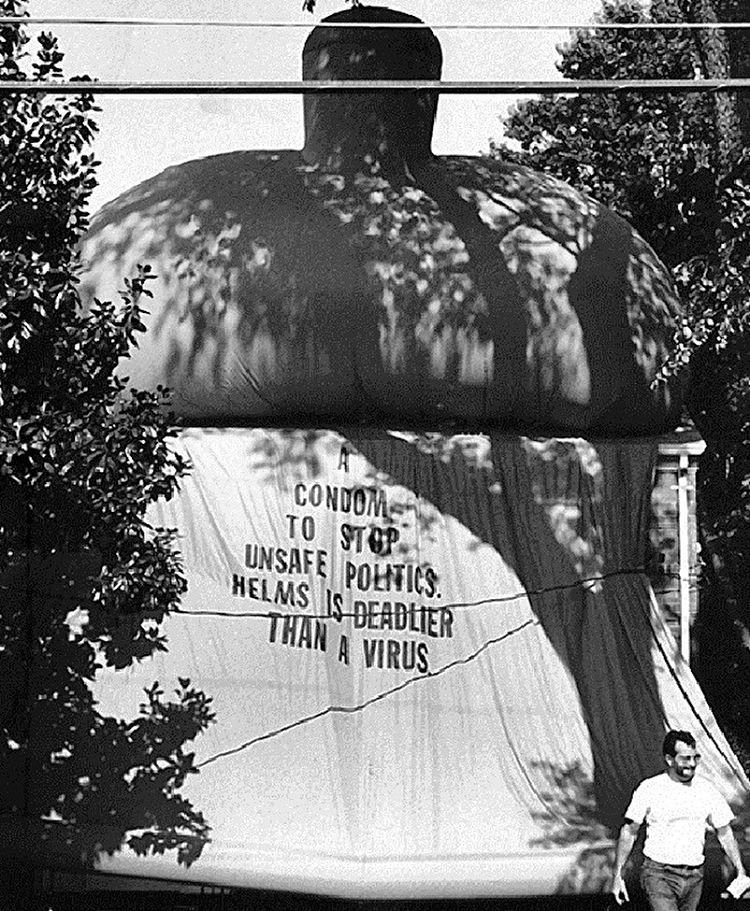

These people fought a plague and an indifferent government with wit (“Your gloves don’t match your shoes,” they chanted at the police who donned latex to assault them, “you’ll see it on the news!”); with creativity (they wrapped Jess Helms’s house in a giant condom); with theater and poetry and performance art and painting and music."

AIDS activists unfurling a giant condom over Senator Jesse Helms' house

"Of course, it’s one thing to believe in Angels in America, to believe in Picasso’s Guernica, and another to believe in your own sloppy first draft, or in a picture book about a monkey. One thing to fight for the first amendment, and another to retweet an invite for your friend’s poetry reading.

... But the exercise of freedom is a de facto defense of that same freedom. Freely making art, and freely talking about the art you made, is valuable in and of itself when free expression is being eroded. If anyone’s still taking that freedom for granted, it’s time to wake up and smell the history.

Write while you can. Paint while you can. Spread your art through the world. Not everyone is so lucky. Publish books and read books and teach books while you can. Take the art you love and blast it from your trumpet. Shout into the wind the names of the things you love."

–Rebecca Makkai, from her essay "The World's on Fire. Can We Still Talk About Books?"